Paul O’Connor, esteemed newspaperman and professor, makes it a practice not to review – or even to finish reading – books he really doesn’t like. Keep that in mind as you read his take on a historical novel about books and authors in Paris a century ago.

Reviewed by Paul T. O’Connor

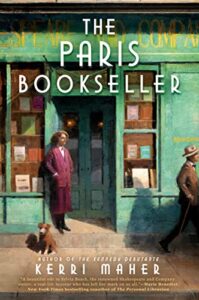

THE PARIS BOOKSELLER. By Kerri Maher. Berkley. 306 pages. $26, hardcover.

For fans of The Lost Generation, Kerri Maher’s The Paris Bookseller offers the prospects of an exciting inside look at the authors we most cherish a century later, all wrapped around the inner story of a miracle-working bookseller.

For fans of The Lost Generation, Kerri Maher’s The Paris Bookseller offers the prospects of an exciting inside look at the authors we most cherish a century later, all wrapped around the inner story of a miracle-working bookseller.

Unfortunately, this historical novel delivers something short of what we might expect.

Sylvia Beach is a name often overlooked in literature lectures about that era, but her bookstore and lending library may have been as important to this generation of authors as the salons of the much-better-known Gertrude Stein. An argument might also be made that, in publishing James Joyce’s Ulysses despite powerful opposition, Beach made the greater contribution to 20th century literature.

The Paris Bookseller opens in 1917, as World War I rages in France. Beach arrives in Paris from the United States and finds an exceptional bookstore, A. Monnier Bookseller, at 7 rue de l’Odeon. There she befriends – actually falls in love with — the owner, Adrienne Monnier, and acquaints herself with the many artistic luminaries who frequent the shop.

Beach returns to Paris in 1918 after a stint in the Balkans and has an idea: Open an English language bookshop and lending-library around the corner from A. Monnier.

The rest is history: The shop, Shakespeare & Co., is an immediate modest success. It draws all nature of American ex-pat, British and European customers and becomes the so-called “third place” for many of the people who now populate our Norton anthologies of 20th century literature.

Joyce is chief among them. He has been serializing chapters of his Ulysses in an American literary magazine but has been unable to find a publisher for the complete book. U.S. prudishness has led to the Post Office’s seizure of the magazine and a trial of its two publishers on smut charges. No publisher will touch the book.

Beach publishes it herself, a demanding undertaking that nearly breaks her financially and emotionally. This is also when we come to understand that working with Joyce is not easy.

While that’s the main story line of Maher’s book, there are others. There are Beach’s relationships with her mother, her sister and with Adrienne. Ernest Hemingway pops in and out of the book. F. Scott Fitzgerald and Zelda make cameos. John Dos Passos ventures by, as do photographers, composers, conductors, all sorts of gifted people.

Because of this, the novel lacks focus. While Ulysses is the most prominent storyline, the novel is not about the publication of that masterpiece. There are too many storylines, many of them uninteresting and too brief. Or uninteresting and too long. One might argue that the main storyline is the challenge of keeping a bookstore afloat. If so, that needed greater emphasis.

The answer to that criticism, of course, is to say, “if you are going to write a biography of a person, you have to include all of those storylines.” But this isn’t a biography. It is a piece of historical fiction, and it does not work well as such.

The Paris Bookseller represents a lost opportunity. The material has such potential as a piece of creative nonfiction, where Maher could have used the wealth of prime historical material she researched in a biographical sketch. The read would have been much truer.

Another problem lies in Maher’s fictional dialogue. The conversations between Sylvia and Adrienne sound contrived – the lovers speak in complete sentences, all the time – and there is no depth to the relationship she presents us with. As for Hemingway, Maher has him sound like a game-show host, as if he were a pleasant and untroubled guy!

There’s the problem with this review: It reads as if I hated the book. But I made myself a promise a few years back: If I really hate a book, I stop reading and return it to the shelf. I didn’t do that.

This may be a flawed piece of fiction, but the nonfiction in it is sufficiently interesting that I plodded on to page 306, and then read the author’s note, as I suspect others will, too.

Readers may be disappointed, but not entirely.