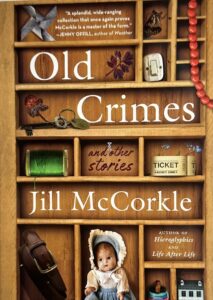

OLD CRIMES. By Jill McCorkle. Algonquin Press. 241 pages, $27.

Any reader of literary fiction will relish the stories in Jill McCorkle’s latest collection. Once again, this North Carolina writer demonstrates the same sense of detail, depth of perception, and artful composition that have marked her ouevre over the years. These are elegant stories, but not pleasant ones. Pain, confusion, regret, disappointment along with McCorkle’s wry humor reign in the pages of Old Crimes.

“The Lineman” laments the mistakes he made that led to the demise of his marriage. Now, he feels the distance between him and the modern world of information flow, while he maintains the infrastructure of the old communication — and he struggles to stay in touch with his daughter. A woman who lived with a “Swinger” for three years wanders the house that the man’s wife will soon evict her from. His swinging days were long gone, but she found a box of polaroids, pictures of his many lovers. She is not included. She wonders if she can get her picture in there before she has to leave. A young couple buys a “Confessional” at an antique store and uses it as a party diversion in the middle of their house. After the novelty wears off for their friends they continue to use it personally, only to discover that what is spoken in the CONFESSIONAL needs to stay in the CONFESSIONAL. They return the antique to the store.

The author uses a couple of devices throughout that heighten the narrative. An activist mother and school librarian begins an Easter custom, walking the stations of the cross in her yard, stopping at each one to articulate a concern. She’s so witty that people stop by to listen, and she becomes an attraction over the years. The story starts offs in plum times, but McCorkle slips in just a hint of shadow, the future disabling of the husband, then returns to the narrative. With that coloration added, later she has the woman, now retired, at The Last Station lamenting the thousands of peanut butter sandwiches she has made, the many children whom she selflessly nurtured when they needed her, the lamp she didn’t like that she got when she retired — and the fact that her husband never told her he loved her before he died. All of this is verified by her daughter, a witness who serves to heighten the poignancy of her mother’s pain by supplementary observation. McCorkle’s unobtrusive construction brings us to a sharp moment of recognition again and again.

Perhaps the most poignant portrayal is the high school drama teacher who finds herself seeing her life as a play, “…with a badly written third act.” She calls it “Family Gathering,” and the cast is her grown family, the setting a vacation at the old resort hotel they visited most summers. The hidden fact: a “flicker” in her brain that is growing and shades the narrative. McCorkle deftly blends the principles the woman taught in her acting classes with the life she has lived, parallels and relations cropping up each day, the author throwing light by making dramatic turns out of quotidian family interactions. The result is, oddly enough, a viable acting precis, as well as a path to the denouement, where the teacher likes “…to think that leaving will be like breaking the fourth wall, stepping down-stage into the footlights and then out of view.” This piece, like the others, contains priceless sentences that showcase McCorkle’s exceptional talent.