Reviewed by Linda C. Brinson

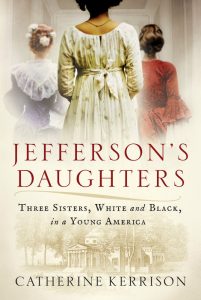

JEFFERSON’S DAUGHTERS: Three Sisters, White and Black, in a Young America. By Catherine Kerrison. Books on Tape (Penguin Random House Audio). Read by Tavia Gilbert. 17 hours; 14 CDs. Also available in print from Ballantine Books.

This ambitious book by Catherine Kerrison, who teaches history at Villanova University, is, in a way, several books in one.

This ambitious book by Catherine Kerrison, who teaches history at Villanova University, is, in a way, several books in one.

Kerrison combines her two scholarly interests – colonial and Revolutionary American history, and women’s and gender history – in a remarkable feat of research and also of imagination.

The book is all nonfiction, to be sure, but where there are gaps in the information available, parts of the story that, apparently, no amount of diligent research can fill, Kerrison surmises what she cannot know.

By book’s end, Kerrison has made her case that the unknowable parts of the story are at the heart of the era she’s describing – a time in American history when slaves and women, even white women, were not really considered to be among those people who had been “created equal” and whose voices were worth hearing.

Early on, the book is an interesting account of what’s known of the lives of Martha and Maria Jefferson, the only two children born to Jefferson and his wife, Martha Wayles Jefferson, who survived to become adults, or even teenagers. Widowed early, Jefferson took considerable interest in the education of his daughters, but because he was so embroiled in the affairs of the colonies as they became a nation, he was often separated from the girls.

Drawing on available sources, Kerrison can tell us most about Martha, the elder by several years, who accompanied her father to Paris and attended a convent school for well-to-do young European ladies there. Martha married young after returning to Virginia with Jefferson, raised a large family, spent much time at Monticello and lived into her 60s, with her latter years complicated by Jefferson’s having lost his fortune and their home,

A bit less is known about Maria, the younger sister, who was left with relatives in Virginia before eventually being brought to Paris for a much shorter stay. Kerrison describes the distinct differences in the two sisters’ experiences and how those experiences helped shape them into very different young women. Sadly, Maria died early after the last of several problematic pregnancies, leaving one child who had almost no memories of her, and little written record.

Kerrison’s recounting of the brief life of Maria and the early years of Martha, while fascinating, get confusing at times, especially when listening to the audio version of the book. I found myself wondering at what point in Martha’s experience various things were transpiring in Maria’s life, particularly after Martha had married and had a rapidly expanding family.

Kerrison begins to delve more into educated speculation when writing about the life of Jefferson’s other daughter, Harriet, who was born to the slave Sally Hemings, with whom he had a long relationship. That relationship began when Sally, then a teenager herself, was chosen to accompany young Maria on her voyage across the Atlantic to join Jefferson and Martha in Paris. The Hemings family already had complicated ties with the Jeffersons; Sally was the half-sister of Jefferson’s late wife; they shared a father.

Living in Paris where laws dealing with slavery were different, young Sally was apparently able to strike a deal with Jefferson that cemented the Hemingses’ special status at Monticello. Harriet, born in the early days of Jefferson’s presidency, had a privileged childhood for a slave. Sources indicate that although she was never officially freed, she was allowed to leave Monticello when she was 21 and given some help on her trip north. Her younger brother, Madison, offered the information in the 1870s that his sister was “passing” as white and was married to a prominent man in Washington, D.C.

Kerrison had some basic information about Harriet’s early years from the records Jefferson kept, in which he briefly mentioned her in his accounts dealing with slaves. But much of what she tells us about Harriet is based on information she knows about other slaves and life at Monticello. She used such phrases as “might have” frequently.

Inspired by Madison’s claims, Kerrison pored through available records in the Washington area, trying to establish Harriet’s new, white identity. That part of the book becomes more like an academic detective story than biography or history.

Toward the end of the book, she philosophizes about the lives of slaves and women at the time and, to a lesser extent, today. Throughout the telling, she strives to be fair, pointing out the ways the white Jefferson daughters’ lives and fortunes were limited by their sex, but also pointing out how much better off they were than slave women.

Jefferson does not look particularly admirable in this book. Kerrison bluntly talks about how the education he wanted for his two white daughters was nothing like that he wanted for his sons. He never would have considered including them in the university he established at Charlottesville, except on social occasions. They were to be educated for their role in society, which was to be wives and mothers and ornamental additions to social occasions. And she bluntly talks about his attitudes toward his slaves, not accepting the often-expressed notion that he was always a benevolent master. Although there were rumors and even news articles about the belief that the “yellow children” at Monticello were his, and although he apparently afforded them special status, he never acknowledged them.

The effect is to present Jefferson as a visionary with high ideals, the author of the Declaration of Independence – but also a man of his times and place, a plantation owner in Virginia, who apparently did not think that equality and freedom should apply to anyone other than white men.

The earlier parts of the book will probably be more pleasing to readers and listeners who like history as story than will later chapters. Overall, though, this is much more an academic book than a popular history. It is a book that will be informative for the majority of Americans who have only a superficial knowledge of Jefferson’s personal life and thought provoking for anyone who takes the time to read it.