Reviewed by Linda C. Brinson

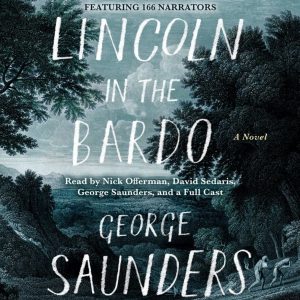

LINCOLN IN THE BARDO. By George Saunders. Read by Nick Offerman, David Sedaris and George Saunders, with a full cast of others. Random House Audio. 7 ½ hours, 6 CDs. $35. Also available in print from Random House.

George Saunders has earned his literary laurels through writing short fiction, as well as essays. Although he’s been writing for many years, has earned prestigious awards and honors, and teaches in the creative writing-program at Syracuse, this is his first novel.

George Saunders has earned his literary laurels through writing short fiction, as well as essays. Although he’s been writing for many years, has earned prestigious awards and honors, and teaches in the creative writing-program at Syracuse, this is his first novel.

And what a novel it is.

In a way, Lincoln in the Bardo is a novel about President Abraham Lincoln and how he dealt with the death of his 11-year-old son, Willie, in 1862, during days that were already grim and distressing as deaths began to mount in the still-new Civil War.

But readers who are looking for a traditional historical novel will not find it here.

In fact, readers who are looking for any sort of a traditional novel will not find it here.

This is a brilliant work of art that, I suppose, is called a novel because it’s fiction, prose, and it’s longer than a short story or novella. But the term novel seems too confining for what Saunders has created.

I listened to the audio version, which, recorded by a large cast of excellent performers and readers, inevitably brings to mind a stage production. The words the characters speak, the actions described, evoke vivid images.

I felt at times that I was listening to, or watching, a Greek chorus, but one that includes some interesting and even disreputable American characters. Another comparison that comes to mind is a stage adaption I saw many years ago of Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River Anthology, a collection of short, free-form poems in which the dead of the small town of Spoon River tell their own stories. This book, however, is much more complex than that.

Saunders builds this book on the historical fact that Lincoln, distraught with grief, visited his dead son in his crypt in a cemetery in Georgetown.

Much of the story is told by ghosts, or spirits of people who are dead but remain on Earth in a sort of purgatory, or in-between state, called the bardo by Tibetan Buddhists. These spirits emerge from their “sick boxes” at night and wander the cemetery, talking, quarreling, reminiscing, seeking revenge and even indulging in bawdy behavior. Part of the tension in the book has to do with whether Willie, reluctant to leave his father, will remain in this in-between state, which we learn is especially terrible for children, or whether he will leave his decaying body and head on to whatever awaits him.

Saunders has clearly done a great deal of research. But unlike most writers of historical novels, who strive to work what they’ve learned seamlessly into their story, Saunders intersperses the accounts of the spirits and descriptions of Lincoln with many direct excerpts from journals, letters and other sources, including his references, complete with footnote conventions such as “op. cit.”

This is not an easy book to listen to, and I suspect it’s equally challenging to read in print. In fact, I stopped after a few chapters the first time I tried, substituting a more straightforward and less emotionally draining book of popular fiction. But something drew me back to Lincoln’s story – I was, I suppose, almost literally haunted by the voices Saunders had presented – and I gave the book another try.

There is much emotion in this book: pain, suffering, love, violence and even, at times, hilarity. Saunders spares nothing as he reveals much about the human condition.

Although I’ve read a fair amount about Lincoln, I never quite realized how terrible it must have been for him to deal with his beloved son’s death even while he was agonizing over whether the war into which he had led the country was worth the lives of the many men – all sons of someone – who were dying on the bloody battlefields.

The unifying theme, and there is a theme in this most unusual novel, has to do with persevering, keeping on with a life that means something, even while surrounded by the reality that human lives, loves and achievements are so fragile, so transitory.