Reviewed by Linda C. Brinson

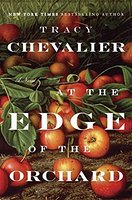

AT THE EDGE OF THE ORCHARD. By Tracy Chevalier. Penguin Audio. Read by Mark Bramhall, Hillary Huber, Kirby Heyborne and Cassandra Morris. 9 hours; 7 CDs. $40. Also available in print from Viking.

I regret to say that I have not read any of Tracy Chevalier’s previous novels, a situation I intend to remedy. If you’re hoping for a review that places her latest novel in the context of her others, weighing against, say Girl With a Pearl Earring, you won’t find that here.

I regret to say that I have not read any of Tracy Chevalier’s previous novels, a situation I intend to remedy. If you’re hoping for a review that places her latest novel in the context of her others, weighing against, say Girl With a Pearl Earring, you won’t find that here.

I had to judge At the Edge of the Orchard solely on its own merits, and this novel has plenty to recommend it.

This is a historical novel divided into two distinctly different parts, separated by a gap of 15 years and most of the continent that was growing into the United States. Both settings – the Black Swamp of northwest Ohio in the 1930s and the California Gold Rush country in the 1850s – are frontiers, though in very different ways, and Chevalier does a fine job of describing ways of life that most of us don’t learn much about in history classes.

Part one is the story of James and Sadie Goodenough, who left Connecticut with their brood of children and headed west. A younger son, James was not destined to be able to make much of a living back home. They set down roots where their wagon got stuck in the mud, and there they tried to establish themselves as farmers so they could claim the land they were homesteading. One of the requirements was to establish an orchard of at least 50 trees, something that James dearly wanted anyway. He loved apples with a passion, and had even brought cuttings from trees that his family back east could trace to England.

The Goodenough family found life in the swamp harder than they had ever imagined. The swamp always seems to be trying to reclaim the land, and in summers, it becomes such an unhealthy place that the family expects the death of a child or two each year. One of their few outsiders they ever see is John Chapman, also known as Johnny Appleseed.

Frustrated by struggles they have no hope of escaping, James and Sadie sink into a pattern of battling each other. Things only get worse as Sadie increasingly finds solace in drinking applejack. Ulimately, a bad situation becomes much, much worse.

Fast-forward 15 years to California, where the Goodenough’s youngest child, Robert, is a 24-year-old making his way in life. Robert is mostly a loner, a man of few words, and Chevalier’s story reflects the way he keeps things to himself. For a while, this second part of the book seems unconnected to the first. We don’t know why Robert left home at such an early age or why he has never tried to return. We learn that he has written occasional letters to his siblings, and that he has not heard back from them.

Gradually, we learn bits and pieces about where he has been and what he has done. He’s worked various jobs before finally lucking into one that suits him: collecting seeds, seedlings and saplings of trees – especially redwoods and giant sequoias – for a naturalist who sells them to people in England who want to create exotic gardens.

Even more gradually, we learn what happened when he left the Ohio swamps. Slowly and carefully, Chevalier brings the two parts of the story together, until an unexpected visitor arrives and the pace picks up.

This is not an easy book to read. Chevalier has done her research thoroughly, and she writes a grim and sometimes violent story. But the novel grows on you and takes hold, until you must know what happens to Robert and the few people he lets himself care about.

The history in this novel is fascinating, especially the story of how those who “discovered” the giant trees in the 1850s dealt with their find.

Trees – first apple trees, then the giant trees of California – are central to the story, in themselves and also as metaphors. Ultimately, the book has much to say about human families, and, to use one of those metaphors, how something fresh and good can be grafted onto what has come before.

This audio presentation of At the Edge of the Orchard, with four readers presenting different points of view, works especially well.