Several students in the opinion writing class in the School of Media and Journalism at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill have contributed book reviews to Briar Patch Books. We welcome these reviews, which offer some different fare as well as fresh perspectives. Thanks to these bright students! Here’s the first one, and we’ll be featuring others in coming days.

Reviewed by Victor James Lewis

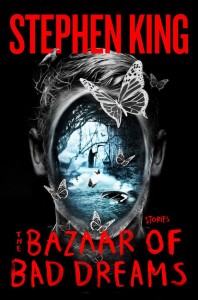

THE BAZAAR OF BAD DREAMS. By Stephen King. Simon & Schuster. 495 pages. $29.99, hardcover

The Bazaar of Bad Dreams is more than the newest collection of short stories from Stephen King – all but two of which have been previously published. Clocking in at a sound 495 pages, the mid-size anthology is a deeply personal entry into King’s bibliography, where he relaxes the pace with notes addressed to Constant Readers, uses the short story as a means of catharsis, and meditates on exactly what it means to die.

The Bazaar of Bad Dreams is more than the newest collection of short stories from Stephen King – all but two of which have been previously published. Clocking in at a sound 495 pages, the mid-size anthology is a deeply personal entry into King’s bibliography, where he relaxes the pace with notes addressed to Constant Readers, uses the short story as a means of catharsis, and meditates on exactly what it means to die.

Death is, of course, the foundation of all horror. We fear what we cannot understand, and nothing is more incomprehensible than the void. King has firmly grasped this concept since the beginning of his writing career, and the stories contained in this collection further illustrate that. Here, however, his musings on death are of a much more mature variety. Trading the blood and gore for ennui and outright suffering for the much more exquisite pain that comes from pushing boundaries and exhausting options, the body count in these bad dreams rises while the screams slowly subside.

King opens with “Mile 81,” a story so clearly designed to be a throwback to what can now be referred to as “classic King” that the effect on readers familiar with his work is almost immediate. All the trappings are there: a seemingly ordinary object that is somehow otherworldly, creeping menace that quickly transforms into outright threat, and visceral depictions of rending flesh and shattering bone. Somehow, though, the storytelling in “Mile 81” is off.

King’s age is beginning to show in halfheartedly constructed scenes where it’s clear he’s trying to set the scene, but uses brand identifiers such as “Amazon Kindle,” “Sbarro’s,” “Double-Stuf Oreos” or even ham-handed references to the comic book “Locke & Key,” written by his son, Joe Hill. Instead of allowing the reader to more clearly visualize as intended, these direct commercial references detract from the experience. To a younger reader, King can occasionally come off as sounding out-of-touch, like a boardroom executive who desperately wants company promotional videos to “go viral on YouTubes.”

Nevertheless, the question of whether King is or is not in tune with today’s world is not the focus, here. King skillfully showcases what has been on his mind since 2009, putting on a master class of short fiction designed to play on what King is best at: making his readers uncomfortable. King has always shone brightest close to home, and that’s probably why he hasn’t strayed too often in his illustrious career as a popular novelist. King himself admits that writing short stories is more disciplined work, but he makes it seem almost effortless.

King knows about small towns, and about people. He excels at painting a portrait of his characters in just a few lines, and leaving just enough blank space for each Constant Reader to interpret as he or she wishes. Through the story, we get more pieces to the puzzle, but the beauty has always been in the mystery. King’s small towns are perfectly illustrated microcosms of American evil, where darkness lurks beneath porches and in dimly lit cellars and in the hearts of human beings alike. Here, that blackness is on full display. King knows what gets under the skin, and at the age of 68, what’s getting under his skin is The End.

Some collections of Stephen King short fiction have a theme. “Full Dark, No Stars” was about marriage. “Hearts in Atlantis” consisted of his thoughts surrounding the Vietnam War. “Different Seasons” was about coming of age and the changing of the times, and “Everything’s Eventual” was concerned with what went on outside the boundaries of our particular reality.

Here, the theme is unerringly human. “Morality” takes the basic idea behind “An Indecent Proposal” and adds in an element of violence that sparks a chain of events that burns a previously almost-happy marriage to the ground. “Bad Little Kid” makes the murder of a child the only sane thing to do. “Batman and Robin Have an Altercation” frames a father afflicted with Alzheimer’s and his son in a situation that seems entirely likely and utterly insane in equal measure. Some of the stories seem out of place in a way that can only be described as “clunky.” They try to fit in and spin a story, but fail in some small way that detracts from the overall experience. However, as anyone who has read King before knows, for every failing like “Tommyknockers,” there is a masterpiece like “The Stand,” and for every “From a Buick 8” there is a “Christine.” When King hits his stride, the reader can feel it.

There are more stories in this collection worth positive mention, but what every Constant Reader, both experienced and new to the fold, needs to take away is this: “Bazaar of Bad Dreams” is meant for the Constant Reader. Each story opens with a note from King, explaining how it came to be. Answering the question that every writer gets asked most often: “where do you get your ideas?” King wants you to know where they come from, and he wants his audience to know that they’ve thought of them, too.