Steve Wishnevsky of Winston-Salem is a man of many talents. Besides being a prolific writer, astute reviewer and sage observer of the political scene, he also is a gifted luthier. He crafts beautiful instruments of wood.

So when Steve is swept off his feet by a book, we need to pay attention.

By Stephen Wishnevsky

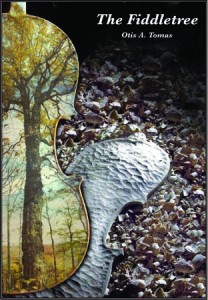

THE FIDDLETREE. By Otis A. Thomas. (www.fiddletree.com) 2011

This is a wonderful book, full of wonders. It is almost unimaginable that one man, even aided by his wife, Deanie Cox, could make such a work of art.

This is a wonderful book, full of wonders. It is almost unimaginable that one man, even aided by his wife, Deanie Cox, could make such a work of art.

It is not generally realized that Lutherie, the making of stringed musical instruments, is one of the most complex and underrated fields of human endeavor. To create a stringed instrument, one must understand acoustics, woodworking, design, finish work, metalworking, chemistry, sculpting, marquetry, algebra and a few other minor details such as electronics and materials science.

Thomas carries this omnivory or omnipotence to an extreme. This book is the story of how one starts with a tree and produces an album of original song compositions. He cut the fiddletree nearly 20 years ago. Locating it in time, space and history on the shores of Cape Breton, he explains the probable history and age of the 250-year-old sugar maple. He tells how he played the tree a song before he felled it.

But his hippie mysticism is well grounded. While waiting a decade for the wood to dry, he reviews the history of musical philosophy from Pythagoras, with an explanation of the “Golden Mean” and similar mathematical aesthetics.

Once the maple is dried, he cuts it on a band saw once owned by Alexander Graham Bell, glues the back, carves it to shape and so on, through the 10 or 20 steps needed to make a violin. He documents each step with his own photography, shows how the top came from a spruce tree on his land, tells you how he harvested resins to make his own pigments for the varnish.

All is explained in the most careful, modest and wise manner possible. This is a mysticism of the sharp chisel, the philosophy of the careful incision.

The middle of the book is a photographic essay of the suite of instruments made from the same tree: a harp, a mandolin, guitar, another fiddle and so on. Thomas walks that fine line between tradition and innovation deftly. Or as we say, “He does good work.”

The last third of the book is a list of the songs, a short explanation of the recording process, an introduction to the other musicians and the sheet music for all the tunes. I assume he wrote the music, too, as well as composed the songs. Many of the songs are memorials to lost friends, and even a brave, if not wise dog, who sought revenge on a pack of coyotes.

Did I say amazing?

The art world may rejoice over pats of elephant dung slapped on gallery walls, but this is enough art for me. I must admit I knew, played music, and perhaps even indulged in intoxicants to excess with Thomas, long and long ago, when the world was young. He is one of a kind, and a great fiddler. Blessings on your hippie heart, old man. Carry on.