Paul O’Connor, a veteran newspaper journalist, finds the account Burkhard Bilger tells of his Nazi grandfather of great interest – and also finds much to like in Bilger’s dogged search for the truth.

Reviewed by Paul T. O’Connor

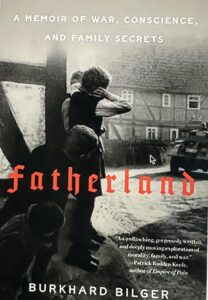

FATHERLAND: A Memoir of War, Conscience and Family Secrets. By Burkhard Bilger. Random House. 279 pages. $28.99, hardcover.

Anyone who undertakes to compile a family history had better prepare for surprises, not all of them pleasant.

Anyone who undertakes to compile a family history had better prepare for surprises, not all of them pleasant.

Burkhard Bilger, a veteran writer for The New Yorker, knew this well when he undertook his search for the story behind his grandfather’s role in World War II.

“Family history is a hazardous thing, footpaths through a darkening wood. It’s a shout in the night and a dash through dim trees, in thin slippers and an old flannel robe, with only a flashlight beam to guide you,” he writes in the opening of the second chapter of his family memoir, Fatherland.

Karl Gonner, Burkhard’s maternal grandfather, was a devoted Nazi and the party chief in a small Alsatian village from the French surrender in 1940 until the town’s liberation in 1944 – and the day he was taken into custody first by the resistance and then by the new French government.

But Gonner, despite his wartime role, was not executed. To the contrary, he was exonerated at trial. It was his grandfather’s story that Bilger wanted to find. He spent 10 years searching for his answers and beautifully writing the story.

Family historians envy the academic historians who are typically researching the lives of people who left behind a trove of documents and secondhand observations. But Karl Gonner was relatively insignificant. A foot soldier during World War I, a wounded veteran and teacher afterwards, a village occupying-officer during the war years. Not much was being recorded about him, and much of what was disappeared either at the deliberate orders of Nazi superiors or in the flames of war.

But not all traces disappeared, and in Bartenheim, Alsace, there were survivors, well along in age when Bilger’s mother, a historian, ventured into the village many years after the war. She took notes and made connections.

Fatherland is, first of all, the story of a German whose life spanned both wars, both losses and both postwar recoveries. It is a rare look at life in small German towns in those years; it is a people’s history of the era, of Gonner’s home village across the border, that village’s social structure and economic plight. Bilger’s account of German life between the wars certainly helps explain why so many Germans fell for the political message presented by the Nazis.

For someone who is writing a family history himself, however, the equally fascinating story here is of Bilger’s search and of the challenges he encountered.

True, he did have the firsthand recollections of a few Bartenheim residents and the retold stories passed on by their sons and daughters, but he openly regrets his late interest in the topic. If only he had begun earlier, he could have interviewed his grandfather himself, and others. Believe me, everyone writing a family history has the regrets of having failed to raise questions while parents, aunts, uncles and friends were still alive.

That the author found so many documents, official reports his grandfather filed with his superiors, family letters, etc., is a testament to his doggedness. He rummaged through repository after repository, often struggling to read illegible German script from the pre-Hitler era.

What he found is nothing short of amazing. And, in the end, he learns why the French did not execute his grandfather. It was a surprise, a nice surprise, the kind of surprise that we often find when we dig into the lives of our family members.