Bob Moyer reviews a book that, both author and reviewer make clear, is not an autobiography. And yet…

Reviewed by Robert P. Moyer

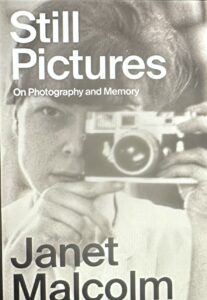

STILL PICTURES: On Photography and Memory. By Janet Malcom. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. 155 pages. $26.

Janet Malcolm wrote many New Yorker articles as well as many books about interesting subjects—Gertrude Stein, Chekov, psychoanalysis, photography, murders. If the subject was uninteresting, she prided herself on finding something interesting about it. There was one subject, however, that she found terminally uninteresting —herself. In an article titled “Thoughts on Autobiography from an Abandoned Autobiography,” she wrote: “I have been aware, as I write this autobiography, of a feeling of boredom with the project …. If an autobiography is to be even minimally readable, the autobiographer must step in and subdue memory’s autism, its passion for the tedious.” She continues to rail against the subject in the book under consideration here, calling memories with a plot the “…original sin of autobiography,” stating that “Autobiography is a misnamed genre; memory speaks only some of its lines.”

Janet Malcolm wrote many New Yorker articles as well as many books about interesting subjects—Gertrude Stein, Chekov, psychoanalysis, photography, murders. If the subject was uninteresting, she prided herself on finding something interesting about it. There was one subject, however, that she found terminally uninteresting —herself. In an article titled “Thoughts on Autobiography from an Abandoned Autobiography,” she wrote: “I have been aware, as I write this autobiography, of a feeling of boredom with the project …. If an autobiography is to be even minimally readable, the autobiographer must step in and subdue memory’s autism, its passion for the tedious.” She continues to rail against the subject in the book under consideration here, calling memories with a plot the “…original sin of autobiography,” stating that “Autobiography is a misnamed genre; memory speaks only some of its lines.”

In other words, this, her last book, is not an autobiography. It is, rather, a collection of 26 digressions based on more than 50 pictures, snapshots “…of no artistic merit,” “…drab little photographs,” which “…if stared at long enough, begin to speak to us.”

They certainly speak to her, and carry her to unexpected places. A picture of her between her parents’ heads, “The Girl in the Train,” but she has no memory of being on the train escaping the Nazis. She is there by “…dumb luck, as a few random insects escape a poison spray.” She does remember, however, her life as an immigrant, with “…a painful and shameful reality of my inner life as a child” — internalized anti-Semitism. She ends the story with a recounting of her family’s Jewish history, and the man who took the picture, all very far from the girl in the picture.

As the title tells us, the book is not about just memories, but memory itself. In “Camp Happyacres,” from a picture of people standing around a car, she vaguely remembers the camp, because “The events of our lives are like photographic negatives. The few that make it into the developing solution and become photographs are what we call our memories.” In a story headed with a picture of her friend “Francine,” she recalls the girl looking up from a malted milk and saying “It tastes so good.” “That these unremarkable words should have stayed in my mind while more significant utterances have disappeared is another instance of memory’s perversity.”

Many of the stories jolt us with epiphanies that emerge as she follows the memory. From a picture of “Slecna,” her after-school Czech teacher, she takes us to a crush on a boy she secretly loved, like other girls, who “..unbeknownst to ourselves were grateful for the safety of not being loved in return. The pleasure and terror of that would come later.” In “Skromnost,” a summer institute where she fell in love with a girl before such a thing could happen, she takes us through the charms of the object of her (unacknowledged) affection Then she travels to the street outside the Plaza Hotel, where she sees the girl again, and realizes she is of another class, a “…daughter of wealth and privilege.” The shock was of recognition: “We know so much that we don’t know we know about each other.”

In a book of what she calls “plotless memories,” where she eschews a narrative, a narrative nevertheless emerges. As her daughter points out in an afterword, little Jana, teenaged Jan, grown Janet is “…the observing sensibility whose impressions of the people in the faded photographs form the narrative of this book.” That narrative provides us the picture of a very interesting person — Janet Malcolm.