Paul O’Connor reviews what he calls a nonfiction legal thriller – and warns that reading it might be hazardous to your appetite.

Reviewed by Paul T. O’Connor

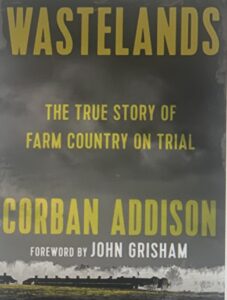

WASTELANDS: THE TRUE STORY OF FARM COUNTRY ON TRIAL. By Corban Addison. Knopf. 464 pages, hardcover. $30. Also available from Random House Audio. Read by Rob Shapiro. 16 hours and 16 minutes.

Spoiler Alert: If you like crispy bacon on your B.L.T. or alongside your scrambled eggs, as I once did, you might not want to read Corban Addison’s Wastelands. Come to think of it, you might not even want to read this review.

Those of us who live in North Carolina know Boss Hog. It’s the epithet applied both to former state senator and hog farmer extraordinaire Wendell Murphy and to the whole pork industry that controls several rural counties in the state’s coastal plain. It’s shorthand for the industrial hog farms that foul the air along the ride to the beach and that occasionally deposit tons of hog feces and thousands of acre-feet of wastewater directly into our streams and rivers.

Those of us who live in North Carolina know Boss Hog. It’s the epithet applied both to former state senator and hog farmer extraordinaire Wendell Murphy and to the whole pork industry that controls several rural counties in the state’s coastal plain. It’s shorthand for the industrial hog farms that foul the air along the ride to the beach and that occasionally deposit tons of hog feces and thousands of acre-feet of wastewater directly into our streams and rivers.

The industrial hog industry settled in the state’s poorest third, moving into much of the farmland that once produced tobacco and other crops, building hog barns that house thousands of animals at a time, and ignoring all concerns for the hell that hog odors, hog trucks and hog spray caused their mostly minority, exclusively lower-income neighbors.

When an industry sets up in a state’s poorest counties with thousands of jobs for farmers and slaughterhouse workers, it can also buy a lot of politicians. And that is what Murphy and others did over the years. One iteration of hog boss led to another bigger iteration and eventually the biggest hog boss in the world, Smithfield Foods, controlled the thousands of farms, several counties worth of local officials, the state legislature and agriculture commissioner, and N.C. State University’s animal science faculty. So, the poor, black owners of small homes and plots in such counties as Duplin and Harnett could complain to the authorities, but they got no help.

No help, that is, until they turned to the courts and a lawyer from Salisbury, N.C., named Mona Lisa Wallace, a veteran of battles for plaintiffs fighting the likes of Duke Energy over unfair customer practices.

Addison has written a compelling legal history of the cases that Wallace, her law firm, and Texas litigator Mike Kaeske brought against Smithfield. It is such a legal thriller that none other than John Grisham wrote the foreword, praising Addison for both his clear communication of the law and his storytelling.

For generations, the families that eventually sued enjoyed their farmland. Most grew up on these properties and inherited the land from their parents. Some of the families went back three or more generations on the same piece of land. One family’s tenure is 100 years old. It was quiet, clean farmland that produced a humble living for its owners.

Then industrial hog operations invaded. Murphy created the business model and made himself fabulously rich. But he also created a system that created an enormous environmental problem – millions of gallons of hog waste without any place to put it.

The solution became open-air waste pits and, when those pits filled, the spraying of the effluent out into the open air. Depending on which way the wind blew, it might land on a neighbor’s house, clothesline or car. No matter where it landed, however, the stench ruined the quality of life for the people who lived in those houses.

There were also the bins used to hold the carcasses of dead hogs, usually uncovered and often positioned at the far end of a farm, close to the property line with residential neighbors. Those hogs, on some farms as much as 10 percent of the stock, died in miserable conditions of filth that betray any idyllic rendering of life on a farm.

Addison takes us through the history of the cases Wallace compiled, the futile attempts to get local and state authorities to help and then the intense legal maneuverings to make a multi-billion dollar, now Chinese-government-owned hog company face the justice system.

Along the way, we will be sickened by reports of just how the hogs who eventually become bacon are treated and the squalid conditions in which they live. We see a company that lies in its press releases and in its court filings. And we see a political system that, for the most part, is rigged to support the bad guy.

Don’t go into this book expecting a balanced presentation. This is advocacy journalism at its most strident. Addison presents Smithfield’s side of the story, but mostly as the straw pig that Kaeske then destroys.

I listened to the audiobook, and Rob Shapiro did a wonderful job. But you won’t want to listen over your bacon and eggs. You might just throw that bacon in the trash.