Bob Moyer likes mysteries, detective stories and other fiction, but he also has a more serious side. In his nonfiction-reading mode, he’s often a student of the Holocaust. This book, he says, is very real – and, thank goodness, also a story of survival and even happiness.

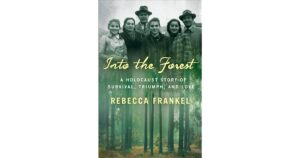

INTO THE FOREST. By Rebecca Frankel. St. Martin’s Press. 335 pages. $28.99.

Authenticity. It’s a quality essential to engaging the reader of nonfiction, reassuring us that the author is not only accurate but also empathic with the subject. That comfort is especially important in stories like the one considered here, in which there is little recorded history, no official records and years of neglect—survivors of the Holocaust who fled to the Polish forests. Author Frankel has traced with the help of two survivors the horrific but compelling survival of the Rabinowitz family. Her fealty to their truth is palpable through the surmises and suppositions that are made about their journey from a village in Poland to a city in America.

Authenticity. It’s a quality essential to engaging the reader of nonfiction, reassuring us that the author is not only accurate but also empathic with the subject. That comfort is especially important in stories like the one considered here, in which there is little recorded history, no official records and years of neglect—survivors of the Holocaust who fled to the Polish forests. Author Frankel has traced with the help of two survivors the horrific but compelling survival of the Rabinowitz family. Her fealty to their truth is palpable through the surmises and suppositions that are made about their journey from a village in Poland to a city in America.

The author begins with a reunion in New York of Mimi, the mother, with a boy whose life she fortuitously saved during a “selection” in Poland during the Holocaust. The author returns to that meeting as a bookend to the travails of the family close to the end of the book. After that introduction, she draws a vivid sketch of the village, the meeting of the couple, their children and village life. With dispatch she then descends into the fear and dread that arrives with the German occupation—the random selections for killing, the constant intimidation, the cruelty of the soldiers. She vividly portrays the desperation of an entire family hiding in a space carved out of the ground beneath the floor boards of a house, a space with not enough room to stand up in let alone move, all for days. Finally, the couple with their two daughters flee to the primeval forest nearby, where they join hundreds of others.

In this 534-square-mile refuge, the story takes on even more urgency. To the family’s advantage, the father is an expert woodsman. To their disadvantage, everyone knows it, and follows him wherever he goes, as the family has to move from place to place to avoid detection. They live in constant fear of discovery, not just from periodic sweeps of German forces, but also Polish collaborators, untrustworthy Russian troops sent to sabotage the Germans, and Polish partisans. Here the detail not available anywhere else arises in the narrative—the daughter who runs through the woods feeling the freedom of running even in the atmosphere of doom, the daughter who steals food from her family for the promise of a trinket from a fellow refugee, the boy with frozen feet who can’t wear his boots. Frankel fleshes out the two-year timeline with details drawn from the family experience and supported with what little research has been carried out. She creates scenes that make us want to look away but compel us to keep watching, until the Russian forces liberate the forest in 1944.

The rest of the story is almost a fairy tale, as the family moves from the devastation of their village to the coast of Italy and then the United States, where they thrive. There, in New York, Mimi meets the boy she saved, and he meets Rochelle, now Ruth, the oldest daughter. They marry, he becomes a rabbi, and then Frankel’s family rabbi since she was five. That is the link that leads to five years of research, much of it sitting in Ruth’s kitchen talking to her. Their relationship, as well as the one with the other daughter, Tonia (now Toby), is the pillar Frankel built her book on, and the source of the authenticity she brings to her narrative. She has backed that research with eight pages of acknowledgments at the end of the book, all to create, as the book cover says, “A Holocaust Story of Survival, Triumph, and Love.” The result is as much of a page-turner as you will read this year.