Paul O’Connor is a longtime journalist who grew up in New England and has spent decades living in North Carolina, observing and writing about government, politics, political machinations and a range of other topics. This time, he’s considering some history that sounds eerily familiar.

Reviewed by Paul T. O’Connor

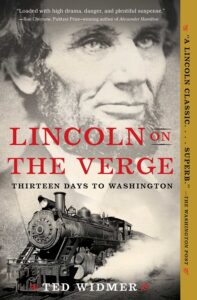

LINCOLN ON THE VERGE: THIRTEEN DAYS TO WASHINGTON. By Ted Widmer. Simon & Schuster. 467 pages. $35m hardcover. Also available in paperback and as an audiobook read by Fred Sanders from Simon & Schuster Audio. 16 hours and 53 minutes.

A new president has won election but, as his inauguration approaches, dangerous weeks lie ahead for both him and his country.

A new president has won election but, as his inauguration approaches, dangerous weeks lie ahead for both him and his country.

In Washington, D.C., at the Willard Hotel, leaders of what today is called the Deep State know that their hold on the political mechanisms of the country, and thus much graft, is about to end. Others from the Slave Power, both in Congress and the executive, fear that their dreams of expanding involuntary servitude to the territories and neighboring countries – and maybe even their ability to maintain slavery in the existing slave states – is in jeopardy.

Plots proliferate, some to seize the government for themselves in a coup d’etat – maybe with the help of outgoing Vice President John Breckenridge — some to murder Abraham Lincoln, most likely as he passes through pro-South Baltimore. Meanwhile, in the hinterlands, armies form to seize control of the capital and country – what we have recently come to know as “legitimate political discourse.”

In his history of the interregnum between Abraham Lincoln’s November 1860 election and March 1861 inauguration, Professor Ted Simon of City University of New York tells a 160-year-old story that eerily parallels our recent experience. But he published this book in early 2020, so it can’t be said that he aligned his storytelling with our most recent insurrection. If anything, we might accuse him of having written the playbook for the “stolen election” crowd.

Lincoln began his journey from his Springfield, Ill., home to Washington in early February. It would take 13 days, cover 1,904 miles over 18 different rail lines, and transit eight states, weaving in and out of Ohio and Pennsylvania several times. He gave 101 speeches to accumulated audiences in the hundreds of thousands, if not more than a million. He shook hands with tens of thousands of people.

In the process, Widmer writes, Lincoln introduced himself to an American electorate that had chosen him without knowing him well. He was coming to Washington intent on upholding the Union and dismantling a corrupt, anti-democratic and insular power structure. And, all along the way, he traveled fully aware that there were significant forces dedicated to murdering him.

Widmer won the prestigious Lincoln Forum Book Prize for this effort, and it is no wonder why. It is clearly written and devilishly conceived. It is a suspense thriller not unlike Frederick Forsyth‘s fictional Day of the Jackal. Just as we know that the Jackal doesn’t assassinate Charles DeGaulle, we know the insurrectionists won’t assassinate Lincoln in 1861. Yet there are times in this reading we can’t imagine how they will miss. It’s one of those “I’ll read one more chapter, then go to bed” books.

Several themes run throughout, in addition to the murder plot concerns. One is that Lincoln used his 100-plus speeches – some five minutes long and delivered from the back of his train to a small-town crowd, others much longer from the dais of majestic venues such as the New York State Capitol in Albany and Freedom Hall in Philadelphia — to make the case for Union. In the process, he projected himself as a new form of political leader: homespun, western, erudite but unpretentious.

Widmer also uses the rail journey to detail the economic differences between the rapidly industrializing North and a stagnant plantation-controlled South. His almanac of railroad and industrial statistics demonstrates the foolishness of the Southern belief that a military victory was possible in an age of total warfare – which is what U.S. Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman eventually brought to bear.

Equally entertaining are Widmer’s many allusions to the characters of both the past and the future who did see, or might have seen, Lincoln along the route. The reader gets a survey of 19th century American history from Widmer’s asides, whether they involve John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, one of the Roosevelt scions, or any number of others. Walt Whitman attends one Lincoln event, and Widmer reports or their mutual admiration for one another.

I listened to Fred Sanders’ excellent narration but then checked the book out of my library to re-read portions. This is a gripping and authoritative read (or listen).