Bob Moyer reviews a book that’s both mystery and thriller, as are many of the ones he reads, but this is a nonfiction book of history.

Reviewed by Robert P. Moyer

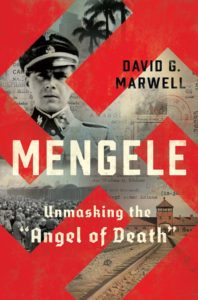

MENGELE: Unmasking the Angel of Death. By David G. Marwell. Norton. 432 pages. $30.

He stood on the ramp, as scores of Jews flooded out of the boxcars at the end of the track in Auschwitz Birkenau. With a gesture of his hand he sent them to work — on the right — or to the gas chamber—on the left. He was not the only one who made “selections.” Every doctor after 1943 was assigned to the duty. Yet he was the most feared, the most remembered by survivors.

He stood on the ramp, as scores of Jews flooded out of the boxcars at the end of the track in Auschwitz Birkenau. With a gesture of his hand he sent them to work — on the right — or to the gas chamber—on the left. He was not the only one who made “selections.” Every doctor after 1943 was assigned to the duty. Yet he was the most feared, the most remembered by survivors.

He was the Angel of Death.

He was Josef Mengele.

He would appear at other sites around the camp and make impromptu selections. He once had a broomstick held up, and children walked up to it. If they went under, they were killed; if they didn’t, they lived. He also made selections that led to horrific experiments — people with blue eyes, with cleft palates, twins. His legend increased as he eluded capture after the war.

Yet he did not escape the memories of many, including the international organization of twin survivors. They raised such a hue and cry that in 1985 an unparalleled cooperation among Germany, Israel and the United States came about to find him, or what happened to him. David Marwell was appointed director of the American group under the Office of Special Investigations. This well-written book, which reads like a mystery, is his record of that search. Using both forensic and historical methods, the commission approached a number of burning questions: What exactly did he do, why did he do it, and what happened to him after the war? How could one man have inflicted so much horror in such a short time, since he arrived in 1943, and Auschwitz was abandoned in 1945? How could one man think up such evil torture?

Nothing in Mengele’s well-to-do upbringing as the child of a factory owner suggested his future activities. His education was standard for an ambitious, educated young man; he became a doctor, and acquired two other degrees. He became expert in his field, and was encouraged as well as promoted by his mentors, who were the leading experts in his chosen field—phenogenetics, the study of the influence of the environment on genetic properties, and how the genetic properties can be inferred from the phenotypes, or traits. That very description explains his value to the Nazi regime — the word phenogenetics even comes from the German. A central premise of the regime was the superiority of the German volk, and the necessity to separate the inferior races from them. Before the war started, Mengele frequently was called upon to make judgments about whether an individual was of Jewish ethnicity (the length of the jawbone came into play). It is therefore logical that after a stint on the eastern front, for which he was decorated, he found himself in an ideal situation, where he could experiment on a plethora of subjects within the realm of his scientific discipline.

How did he justify the cruelty of his actions? Once again, he simply fell into the dominant premise of the regime. When one of the newly arrived doctors requested to be removed from selection duty, Mengele convinced him to return, pointing out that these were not people, they were an affliction on the volk. In other words, they were already dead. Doctors under the regime, particularly in the elite SS they were members of, were no longer to care for the individual — they were to care for the health of the race. The author illuminates the path Mengele took to the platform at Auschwitz with astonishing and agonizing detail. His argument emerges clearly. Mengele was not an evil aberration who created tortures for the sake of torture — he was the product of an evil system into which he fed the results and products of his experiments. Everything he did was in the name of science.

He escaped after the war. Once the war ends, the book becomes a thriller tracing his exit to South America; a cat-and-mouse game once he settles into a series of refuges in plain sight; and a detective story that demands a lot of shoe leather as they search for a man reported to have died in 1985. The political intrigue is thick in the finale of the book, as the tension among the three countries involved suggests. Yet even after all the incontrovertible evidence that piles up, even given the assuredness of Marwell himself, the book leaves an iota of doubt—was it Mengele in that grave? The only thing we can be certain of is that he eluded capture, and justice for all his victims. Marwell does indeed unmask the Angel of Death, who would be shocked to the core that every tenet he held has been proved false — whatever race we are, we are 93 percent like everyone else. We are not different.

(Don’t be put off by the book’s length. 83 pages are Notes and Index.)