Tom Dillon, journalist and outdoorsman, reviews a new book that’s full of information about North Carolina’s beloved tourist attraction and state park.

Reviewed by Tom Dillon

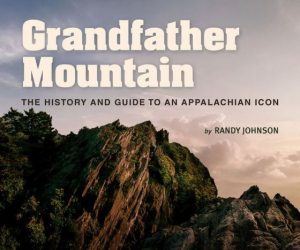

GRANDFATHER MOUNTAIN: THE HISTORY AND GUIDE TO AN APPALACHIAN ICON. By Randy Johnson. University of North Carolina Press, 290 pages, $35.

Mention Grandfather Mountain near Linville, and the face of the late super-promoter Hugh Morton inevitably springs to mind. It was Morton who promoted North Carolina’s “top scenic attraction,” as it was known, came up with the idea of the Mile-High Swinging Bridge (only 80 feet above the ground, but a mile above sea level), and eventually became one of the best-known North Carolinians of the 20th century.

Mention Grandfather Mountain near Linville, and the face of the late super-promoter Hugh Morton inevitably springs to mind. It was Morton who promoted North Carolina’s “top scenic attraction,” as it was known, came up with the idea of the Mile-High Swinging Bridge (only 80 feet above the ground, but a mile above sea level), and eventually became one of the best-known North Carolinians of the 20th century.

But Morton isn’t the only name one should associate with the mountain. A more obscure name is that of Randy Johnson, a hiker, cross-country skier and backpacker who set up Grandfather Mountain’s self-sustaining backcountry trail permit system in the 1970s and 1980s. It was that system that really saved what at the time was a decaying trail network, as well as laid the groundwork for what is today Grandfather Mountain State Park.

As Johnson tells it, he and some friends had come to the mountain sometime in the 1970s hoping to do some winter camping and hiking – looking for “the snowiest, most spectacular summit in the South” – only to find the trails closed. There had been a death from hypothermia on a poorly maintained trail, it turned out, and Morton, ever averse to bad publicity, had closed the trails. To him, it had seemed the only option.

“I couldn’t imagine the possibility that the mountain’s highest peaks would be off-limits to hikers,” Johnson writes here, “so I set out to meet Morton. Luckily, he was receptive to a hiker fee-funded, safety registration program I devised to keep the trails open.” Johnson ran that program for more than a decade, reopening old trails and blazing new ones, teaching cross-country skiing, promoting backcountry management, and all the time, writing about it.

He’s still a writer for a several outdoor magazines, as well as author of a number of hiking guides, but this is the book he was destined to write, and it’s a good one. His history follows that of northwestern North Carolina through the travels of the early botanists, on through settlement (yes, there’s stuff about Tweetsie Railroad), the logging years, then into the development of resorts (some good, some bad) and finally through to the emergence of a conservation ethic.

The book reliably follows the battle between Hugh Morton and the federal government about the route of the Blue Ridge Parkway in the region. That’s the fight that ended with the agreement to build the Linn Cove Viaduct over a part of the delicate high-altitude environment. It was a definite battle, and Johnson says Morton’s feelings are probably one reason the mountain’s backcountry is today a state park, instead of parkway land.

There’s also the inevitable information about the swinging bridge and other tourist attractions, which remain under the control of the Morton family and friends. That was one of the compromises that had to be worked out when the backcountry was sold to the state for a new state park. It’s a tourist attraction, but it has been done with more care than a good many others.

One caveat: Don’t expect to tuck this into your back pocket for a hike. It has information about all the trails, old and new, as well as some Johnson would like to see that don’t exist yet. There are also handy tips on photography. But at 9-by-12 inches and loaded with color photography, this is a coffee-table special. It’s a coffee-table special with a lot of information and history, but it’s still a coffee-table book.

But the main point is Johnson’s optimism about the future of the mountain now, with new state protections against development and new state support for the trails. “My hope,” he says, “is that the wild beauty still found on the mountain’s peaks … will open a door to appreciation and inspiration for whoever finds their way to our great, evergreen Grandfather.”

- Tom Dillon is a retired journalist in Winston-Salem.