Our references to history can be as selective as our use of current “facts.” Paul O’Connor takes a look at a recent book that tells the uncomfortable story of the Roosevelt administration’s dealings with Jews and other refugees before the U.S. entered World War II.

Reviewed by Paul T. O’Connor

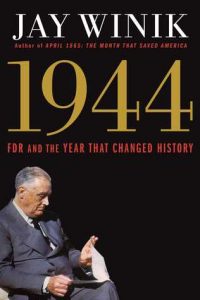

1944: FDR And The Year That Changed History. By Jay Winik. Simon & Schuster. Hardcover. 536 pages. $35.

While Donald Trump has been denigrating immigrants and insulting Muslims, the political left has been countering with references to America’s supposedly accepting tradition of the world’s tired, poor and huddled masses.

While Donald Trump has been denigrating immigrants and insulting Muslims, the political left has been countering with references to America’s supposedly accepting tradition of the world’s tired, poor and huddled masses.

But the left does not mention America’s history regarding the Holocaust, the MS St. Louis or internment camps for Japanese Americans.

Jay Winik does in his newest book.

Just before, and then during World War II, the U.S. State Department and the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt brushed aside Jews and other European refugees and refused to directly intercede to either stop or slow the Holocaust.

In his 2015 book, 1944: FDR and the Year that Changed History, Winik tells that story, but one would never guess that from either the title or book’s cover jacket.

This is part FDR mini-biography, part story of his dealings with Josef Stalin and Winston Churchill, part recap of American action in the European theater of WW II, and, biggest part, part history of American policy toward immigrants, especially Jews, during the years when the Nazis were preparing for, and then executing, the Holocaust.

FDR knew long before the outbreak of war in 1939 that Jews were being persecuted in Germany. And after the war began, he received credible reports that Jews were being removed from their homes and sent to camps. As the war ground on, Winik demonstrates indisputably, Roosevelt learned that Jews were being murdered on an industrial scale at Auschwitz.

Yet FDR did nothing.

In the years before America’s entry into the war, FDR refused to push for liberalization of immigration policy to allow Europeans of all religions to escape to America, turning away the MS St. Louis and its approximately 1,000 Jewish refugees in 1939. (They eventually returned to Germany.) And, he refused to act in subsequent years as the U.S. State Department constructed artificial barriers to keep immigration below even that permitted by law.

After the war began, FDR refused to take action when evidence smuggled out of Auschwitz clearly demonstrated industrial scale murder. And, with regard to the Japanese-American internment camps, FDR refused to intervene when it became obvious that they were unnecessary.

Winik tells us, as all historians do, that FDR was a master politician, one who knew how to play the game to get what he wanted, and what he wanted most was to defeat the Axis powers in Europe and the Pacific. He and his defenders repeatedly said that the best way to save all European civilians was to win the war quickly. They considered any diversion of resources from the immediate goal of destroying German military forces as unwise. Besides, they said, there was nothing they could do about the camps.

Winik thoroughly disproves American postwar claims that the camps and rail lines leading to them could not have been bombed. American bombers flew right over Auschwitz and several times hit the camp with errant bombs intended for nearby industrial targets. He also undermines arguments that the rescue efforts initiated late in the war, efforts that did save thousands of lives, could not have begun earlier, thus possibly saving millions more.

FDR’s policy toward the Jews doesn’t fit the record of a man who worked so hard to help the weak and the poor. What explains it?

Winik suggests that, given anti-immigrant and anti-Semitic attitudes afield in the U.S. in those years, FDR was afraid that efforts to rescue the Jews would cost him political capital at home, and, further, that that loss of capital would hurt the war effort.

The Jewish account and discussion, on their own, are good reason to read Winik’s book. But the rest of the book is neither original nor cohesive. The reader could get the idea that Winik restructured four or five ideas for short books and tied them into one big one.

Then there is the question of the misleading title. Why that title when the book is mostly about the Holocaust and refugees? Maybe the publishers decided that Americans aren’t any more interested in refugee issues today than they were during World War II.

- Paul T. O’Connor, contributing editor, is a university lecturer who is available for freelance writing assignments. Contact him at ocolumn@gmail.com.