It’s worthwhile to learn history, and to learn from history, and especially, as Paul O’Connor observes, to see how yesterday’s mistaken attitudes persist today.

Reviewed by Paul T. O’Connor

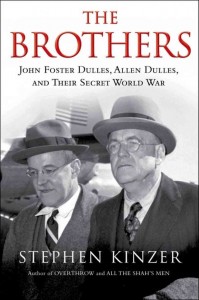

THE BROTHERS: JOHN FOSTER DULLES, ALLEN DULLES AND THEIR SECRET WORLD WAR. By Stephen Kinzer. Read by David Cochrane Heath. Blackstone Audio. 13 hours, 28 minutes. $14.95 (Audible.com)

Americans want to think better of out 20th century history than our adversaries portray it, to deny Soviet charges of imperialism, Chinese allegations of hegemony, and Cuban characterizations of us as the neighborhood bullies.

Americans want to think better of out 20th century history than our adversaries portray it, to deny Soviet charges of imperialism, Chinese allegations of hegemony, and Cuban characterizations of us as the neighborhood bullies.

Such a disposition will be hard to maintain for anyone who reads Stephen Kinzer’s 2013 history of John Foster Dulles and Allen Dulles, the immensely powerful brothers who controlled the U.S. Department of State and the Central Intelligence Agency during much of the Eisenhower administration and who jointly waged a war, mostly kept secret from the American public, against nations across the globe.

Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and CIA Director Allen Dulles had been raised in a family tied closely to the American international establishment, and they both worked as prominent lawyers in New York. They used their political connections to serve their clients in ways that would constitute illegal conflicts of interest today.

In the wake of World War II, the brothers were well situated to play major roles in America’s relations with the world. Allen Dulles had been a successful intelligence agent during the war, and John Foster Dulles was recognized as one of the Republican Party’s leading minds on foreign affairs.

Dwight Eisenhower’s election in 1952 propelled the brothers to power, and they used it with brutal and myopic determination.

John Foster Dulles was an ardent advocate of global corporatism – the belief that small countries must oblige the interests of large international corporations. He operated with Calvinist certainty, especially regarding American exceptionalism, the belief that America is blessed with permission from God to run the world.

Allen Dulles, although sharing his brother’s political views, was in personality the complete opposite of his restrained brother. A social butterfly, charming story teller and mischievous cad, his skills as an intelligence agent were undeniable, but he was a terrible administrator, an inadequacy that would cost the U.S. dearly many times, especially in 1961 in the Bay of Pigs operation.

Once in office, the two often bypassed regular channels to conduct secret operations that served their paranoid view of the world. In Iran, Guatemala, Indonesia, Indochina, The Congo, Cuba and other countries, they fomented rebellion and pursued the interests of their global corporate friends.

The Dulles brothers failed to understand what was becoming the post-colonial world that followed WW II. As nations freed themselves from the yokes of England, France, Holland and Belgium, and attempted to assert domestic control of foreign corporations on their soil, they sought to develop their own national identities. They preferred neutralism in the Cold War between the Soviet and Western blocs. But the Dulles brothers said that those who were not with the U.S. were against the U.S.

In one nation after another, the brothers saw sincere nationalist movements as communist insurrections, sometimes, as in Indonesia, despite forceful protestations, by these countries’ leaders, of affinity for the U.S. and the West. And once a Dulles enemy, any such country could count on U.S. interference in their domestic affairs, including the arming and bankrolling of insurrections.

Kinzer doesn’t lay all the blame on the brothers. He clearly states that they were carrying out Eisenhower’s vision of how to conduct world affairs. And, in a spectacular closing chapter, Kinzer places the Dulles brothers in the context of American 1950s insecurity.

Unfortunately, the Dulles mindset persists today, fueled by politicians who tell the gullible Right that the U.S. can and should always have its way when dealing with other nations, that compromise is not necessary. Other countries should bend to our will.

This well researched and argued book is worth a read or listen.

- Paul T. O’Connor, contributing editor, is a university lecturer who is available for freelance writing assignments. Contact him at ocolumn@gmail.com.