With Cuba about to be much in the news, Paul O’Connor reviews a 2008 book that should help put the coverage and discussions into accurate perspective.

Reviewed by Paul T. O’Connor

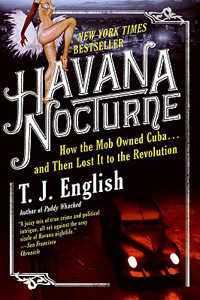

HAVANA NOCTURNE: HOW THE MOB OWNED CUBA AND THEN LOST IT TO THE REVOLUTION. By T.J. English. Read by Mel Foster. Audible.com. 13 hours and 19 minutes. $26.59

In the course of American history, Cuba has been our femme fatale. The island is just 90 miles off our coast, with so much beauty and potential that we just can’t help ourselves. We keep getting involved with her, and it never turns out well.

In the course of American history, Cuba has been our femme fatale. The island is just 90 miles off our coast, with so much beauty and potential that we just can’t help ourselves. We keep getting involved with her, and it never turns out well.

Southern slave owners fomented revolution in Cuba before our Civil War with an eye to making it an American state. Cuba was the trigger for the Spanish-American War. Americans squashed a revolution there in the early 20th century, and then there was that whole thing with the Bay of Pigs, the missile crisis and the ongoing embargo.

With President Obama’s coming trip to Cuba, we’re about to become enmeshed in another round of national handwringing, led by the American right and their Cuban-American voters in Florida. The anti-Obama rhetoric might even drown out Donald Trump’s belittling of the two Cuban-American presidential candidates, Sens. Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz.

Before any of us fall for the contrived story of how Fidel Castro and company stole the legitimate property of American businesses and individual Cubans, it would be a good idea to revisit T.J. English’s entertaining and frightening 2008 history of the U.S. mob’s ownership of Cuba from shortly after World War II until the revolution succeeded in 1959. English shows no amity toward Castro; the author isn’t selling Fidel as a saint. But this book also exposes the breadth of corruption existent in Cuba up until the very night that Castro’s forces marched into Havana.

Charles “Lucky” Luciano and Meyer Lansky had long eyed Cuba as their dream acquisition. From the early 1930s until 1946, they longed to turn the island into their own criminal state. When, through a fortuitous convergence of events, they were able to establish themselves there in the late 1940s, they wasted neither time nor effort in remaking the country in their own image.

American diplomatic pressure forced the Cuban government to deport Luciano to Italy before much headway had been made, but that left his lifetime business partner Lansky even more latitude to work his magic. In his decade-long run as the leader of mob operations, Lansky gained control of the gambling, hotel and entertainment industries on the island. He developed an offshore tourist destination unrivalled in the hemisphere. While prostitution remained the domain of local mobsters, the American mob conspired with major American companies to run hotels and other industries.

English provides us with a captivating profile of the best-known characters involved: Lansky, Luciano, various members of Tampa’s Trafficante family and Fulgencio Batista Zaldivar, the Cuban dictator, as well as entertainers and minor players who have disappeared from view today. In the end, readers might feel empathy for Lansky in about the same way we did for Tony Soprano.

Cuba’s criminal state went beyond the American mobsters. Many “legitimate” American businesses, some of which are undoubtedly seeking compensation from Cuba today for property nationalized in 1959, were fully and knowingly involved with the mob. Hotel companies, airlines, agricultural endeavors knew who ran the place, who was running the casinos and the shows that drew American tourists. And the extent of the Cuban complicity also can’t be discounted. A lot of people were getting rich, many more had jobs or markets for their goods, and a lot of tourists were having the hedonistic time of their lives.

Cuba and the U.S. are moving toward warmer relations again. As Americans we should view that development not through the prism of rewritten history of a Free Cuba that didn’t exist, but through the reality that when Castro took over, the biggest losers were the mob and their friends.

- Paul T. O’Connor, contributing editor, is a university lecturer who is available for freelance writing assignments. Contact him at ocolumn@gmail.com.