Paul O’Connor reviews a book of history that, as is often the case, is relevant to today’s political debates.

Reviewed by Paul T. O’Connor

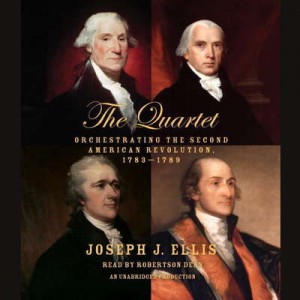

THE QUARTET: ORCHESTRATING THE SECOND AMERICAN REVOLUTION 1783-1789. By Joseph J. Ellis. Read by Robertson Dean. Random House Audio. Nine hours and 20 minutes. $35. Also available in hardcover from Knopf. $27.95.

There’s a six-year gap in the American history that many of us studied in school. It starts with victory at Yorktown in October 1781 and ends with the opening of the Constitutional Convention in May 1787.

There’s a six-year gap in the American history that many of us studied in school. It starts with victory at Yorktown in October 1781 and ends with the opening of the Constitutional Convention in May 1787.

The gap is usually filled with a sentence such as this: “The newly independent states operated under the weak and unworkable Articles of Confederation until a new constitution was written in Philadelphia.”

Unfortunately, current political forces have used the gap to concoct all manner of stories about the intentions of our Founding Fathers, usually to promote right-wing positions.

Fortunately, there’s Joseph J. Ellis, who is probably the finest combination of American Revolution era historian and readable writer. He never comes out and screams “Bull!” to these revisionist historians. He simply lays out the record.

The Articles were a natural outgrowth of the republican spirit of the revolution, a rebellion against a big and distant government. Thus, the Articles placed power in the states, limiting the federal government’s power.

George Washington was one of the first to understand that this form of government would not work. As commander of Patriot forces, he experienced the ineffectiveness of the Continental Congress when it came to financing and executing a war. Alexander Hamilton came from the same perspective.

James Madison grew into his distaste for the Articles, and John Jay came to the same conclusion in his experiences in the diplomatic world.

The Articles did not work in three major areas. The first was finance. Congress had no authority to raise money. If that was the case, then it could not pay the country’s debts or execute the war.

The second was in foreign policy. The European powers snickered at the misnomer “United States of America.” In reality, the states were 13 separate sovereignties.

Finally, there was westward expansion. The Treaty of Paris in 1783 gave the U.S. all lands north of Florida and to the Mississippi. The Articles required the states to give up all claims to western lands. But the weak federal government could not manage expansion and guard against new territories either creating their own countries or aligning with England, France or Spain.

Given this mess, four men, Washington, Hamilton, Madison and Jay, led what was nothing less than an elitist campaign to dispose of the Articles – not reform them – and replace them with a strong, national government.

Ellis presents his readers with a highly detailed history of these years, of the roles each of the four played and how they manipulated events to forge a new constitution that most Americans probably did not want nor understand the need for.

The author’s storytelling ability is as impressive as his historical skills. He engagingly weaves the story’s many strands.

In the process, Ellis provides us with tools to use in current debates on governing. Madison, who probably did more to win approval for the Constitution than anyone else, did not buy the era’s argument that small government worked best, nor that the government was the main threat to our liberties.

Larger government allowed for the expression of more opinions, and the main threat to liberty came from the majority. A strong government would protect the minority from that majority.

Finally, as to the idea that contemporary Americans must follow the framers’ “original intent” when employing the Constitution, Ellis demonstrates that the founders could not agree on so many issues that they purposefully left things unsettled for future generations to decide.

The only original intent of the founders, Ellis concludes, was ambiguity. And that is what supporters of the idea of a living, flexible Constitution argue.

Finally, no one could have narrated this audiobook better than Robertson Dean. He has the necessary gravitas. But this is one book I wish I had read, underlined, taken notes from rather than heard because it is so dense with important insights into our Constitution.

- Paul T. O’Connor, contributing editor, is a university lecturer who is available for freelance writing assignments. Contact him at ocolumn@gmail.com.