Reviewed by Linda C. Brinson

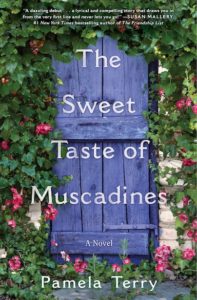

THE SWEET TASTE OF MUSCADINES. By Pamela Terry. Ballantine Books. 288 pages. $27.

Pamela Terry has a winner in “The Sweet Taste of Muscadines,” her debut novel.

Pamela Terry has a winner in “The Sweet Taste of Muscadines,” her debut novel.

The book is billed as a Southern novel, and it is – in the best sense of that descriptive.

The geography is right: The primary setting is Wesleyan, halfway between Atlanta and Savannah, the sort of sleepy Georgia town where there are churches on every street corner and “proper” behavior is still clearly defined, if sometimes hypocritical and often superficial.

Terry’s portrayal of the dynamics and the undercurrents of a small-town society that’s still largely provincial is also right on the mark. She also brings the Southern landscape to life with her detailed descriptions, right down to the tastes and smells of the muscadines referenced in the title.

A lifelong Southerner, Terry demonstrates a deep understanding of the good and bad in that society, and of how the past affects – even haunts – the present.

And while some of the characters you might expect in a novel about small-town Southern life naturally appear in these pages, Terry avoids, to her credit, the easy stereotyping, cliches and exaggerated dialect that mar so many “Southern” novels.

Two of Terry’s main characters, the narrator, Lila Bruce Breedlove, and her brother, Henry Bruce, fled their home for the North as soon as they were able, demonstrating the tensions between past and present, the gap between societal and family pressures and individual preferences and aspirations. Having found fulfilling and creative lives, both are glad to be away from a place where they never felt completely at ease.

Lila, widowed at an early age, lives in Maine, and Henry in Rhode Island. As the book opens, they head home after receiving news of the unexpected – and rather bizarre – death of their elderly mother. There they must deal with their younger sister, Abigail, the one sibling who chose to remain close to their formidable mother, who had been on her own since their father was killed in the Vietnam War.

Lila expects to suffer through a traditional Southern funeral, with more casseroles than they could ever eat, hours of visitation and viewing, and an elaborate service suitable for the widow of a pastor of the town’s prominent Baptist church, who herself was a longtime Sunday school teacher and pianist.

Instead, Lila and Henry find lots of questions surrounding the death, plus their mother’s directive that there be no funeral service at all. When they start probing beneath the surface, they uncover secrets that leave them reeling. They are left to question much of what they believed to be true, much of what shaped their young lives, and much of the family story they thought they knew so well.

Determined to try to find some answers, the two set off on a quest that takes them as far as Scotland and eventually brings them insights and changes the lives of all three siblings.

Before all the secrets begin to emerge, we know that at least on the paternal side, the Bruce family does not date back long generations to antebellum days in the South. Lila’s great-grandfather was a Scotsman who built a successful business of newspaper and radio stations in Ohio before selling out to a media conglomerate and retiring to the coast of South Carolina, where Lila’s Uncle Audie lives now.

That the family is, at least in part, relative newcomers to the South is all a part of this carefully woven plot. In case you don’t get the connection to the quintessential Southern novel and movie, Scarlett O’Hara’s father in Gone With the Wind, Gerald, is no blue-blooded Southerner either, but rather a scrappy Irish immigrant.

When Lila and Henry come upon a Confederate re-enactment in the town square as they arrive for what they think will be their mother’s funeral, Henry blames Margaret Mitchell for the longevity of the myth of the Lost South. Remembering Mitchell’s title words as the movie replayed on TV screens of her childhood, Lila thinks: “For every gray-blooded southerner, they encapsulated a yearning for a world that, in truth, had never actually existed.”

Lila and Henry will learn that much of what they believe about, and grieve over, the world of their childhood similarly was only an illusion. By the end of this fine novel, they understand that the real world is much to be preferred.