Tom Dillon, who’s been known to ski more than a little himself, finds much to like in a new book about a little-known saga of World War II.

Reviewed by Tom Dillon

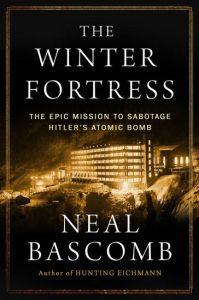

THE WINTER FORTRESS: THE EPIC MISSION TO SABOTAGE HITLER’S ATOMIC BOMB. By Neal Bascomb. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 378 pages. $28 hardback.

The history of skiing is a history of warfare. That’s shown in the earliest Norse sagas, the defeats the Finns inflicted on the Russians in the Russo-Finnish War, even in the exploits of America’s 10th Mountain Division in World War II.

The history of skiing is a history of warfare. That’s shown in the earliest Norse sagas, the defeats the Finns inflicted on the Russians in the Russo-Finnish War, even in the exploits of America’s 10th Mountain Division in World War II.

There’s no more compelling story, however, than in the little-known work of a small band of Norwegian saboteurs and skiers to deny Adolf Hitler the chance at an atomic bomb in 1943.

That’s the story that Neal Bascomb tells in this new book, already optioned to become a major motion picture, and it makes this a rare find – a serious book about atomic energy that is also an absolutely gripping outdoor and winter survival tale.

The saboteurs’ target is a heavy water, or deuterium, plant at Vemork, deep in an inaccessible part Norway. Deuterium was thought at the time to be a necessary moderator of an atomic reaction, and the Norwegian plant was the only one in the world.

The Nazis who took over Norway (and the deuterium plant) may have thought its hard-to-reach location safeguarded it. But they reckoned without the skill and daring of Norwegian skiers and patriots accustomed to living in the wilds.

Much of the action takes place on the Hardangervidda, a cold and high plateau in the Telemark region between Oslo and Bergen. It’s here that one familiar with survival can hide out in the winter, and that’s what the skiers/saboteurs did.

For months, they had to survive alone in the “vidda,” hunting reindeer, foraging for moss, building snow caves, suffering blizzard after blizzard. Then, on the night of the mission, they had to ski for miles, climb a steep cliff, and then escape, all the while under threat of German attack.

It was a mission from which few expected to return. Indeed, the Norwegian and British officers who put together the mission warned them often of that. But few if any backed out.

Neal Bascomb is a New York Times best-selling author of such books as Hunting Eichmann, The Perfect Mile and Red Mutiny, who says he had wanted for years to write about atomic energy. When he happened on the Vemork story, he said, he was thinking about historical fiction. But that changed.

He realized that the story was “a tremendous mix of important history and survival/hunting adventure,” with daring characters, commandos parachuting into enemy-held territory in winter, and high drama. Kompani Linge, as the saboteurs were known, was perhaps a forerunner of U.S. Navy SEALS.

The leading character of this tale is a brilliant academic and reserve ordnance officer named Leif Tronstad, at the time of the German invasion a professor at the Norwegian Institute of Technology in Trondheim. After the invasion, Tronstad worked briefly with the Norwegian resistance, but he was eventually forced to escape to neutral Sweden and then Scotland.

There, he brought the Allies word of what was going on at Vemork, the importance of the plant to the German military – and crucially, how to infiltrate it.

Tronstad recruited countrymen for and eventually became a leader of Kompani Linge, named for a Norwegian Army captain who had been killed in an earlier attempt to wrest part of Norway back from the Germans. And it was Tronstad’s leadership that oversaw everything his saboteurs did – though he had to operate from Scotland and England.

He longed during the entire operation to be on the ground in Norway, instead of directing things from afar, and in the end his hopes were rewarded, as he was able to parachute into Norway and lead resistance toward the end of the war.

But the heart of the book is the work of the commandos on the Hardangervidda and in the small towns around it, surviving in the wild, dodging Gestapo manhunts and risking their lives for their country.

The book’s extensive research involved everything from top-secret documents to old family diaries and letters – as well as much time with the descendants of the men whose exploits Bascomb recounts. And it also included a long interview with the last surviving saboteur, a team leader named Joachim Ronneberg, 96 years old this year.

There’s not space here to go into the many different people who made up Kompani Linge, the details about their families and how they and Norway suffered under German occupation. Indeed, most of the main characters have passed on, and what Bascomb learned was almost invariably second-hand knowledge.

But there is this from Ronneberg, which might well stand as a memorial for all of these little-known patriots: “You have to fight for your freedom and for peace. You have to fight for it every day, to keep it. It’s like a glass boat; it’s easy to break. It’s easy to lose.”

- Tom Dillon is retired journalist in Winston-Salem.