Charles Davenport Jr. of Greensboro, a new contributor, takes a look at a 1993 book that’s much in the news because of a movie adaptation.

Reviewed by Charles Davenport Jr.

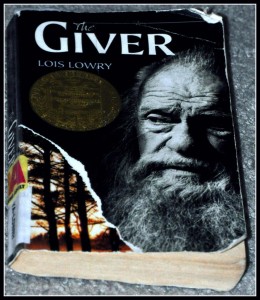

THE GIVER. By Lois Lowry. Houghton Mifflin. 225 pages. $9.99.

In the movie theater about a month ago, I saw an interesting preview for a film called The Giver. Intrigued, I made a mental note. Later the same night, while reading a magazine, I ran across a glowing review of a book by the same name, upon which, I discovered, the movie is based. The next day, as I waited in line for a modem at Time-Warner, I noticed that the young man beside me was thoroughly engrossed in a paperback. Naturally, I stole a glance at the title: The Giver. Minutes later, I received an email alert from one of my news providers: The featured story of the day was an interview with the director of – you guessed it – The Giver.

In the movie theater about a month ago, I saw an interesting preview for a film called The Giver. Intrigued, I made a mental note. Later the same night, while reading a magazine, I ran across a glowing review of a book by the same name, upon which, I discovered, the movie is based. The next day, as I waited in line for a modem at Time-Warner, I noticed that the young man beside me was thoroughly engrossed in a paperback. Naturally, I stole a glance at the title: The Giver. Minutes later, I received an email alert from one of my news providers: The featured story of the day was an interview with the director of – you guessed it – The Giver.

Perhaps this was merely a freakish string of coincidences. Then again, maybe it wasn’t, and I’m not one to defy Providence. I drove straight to the bookstore, purchased a paperback edition of The Giver (originally published in 1993), and raced into “the community” of Lois Lowry’s making.

It is a society free of homelessness, poverty, hunger and pain. Citizens of the community – we never learn its name – lead stress-free lives, because all of their choices are made for them. It’s not even necessary to check the weather forecast: Climate control has eradicated inclement weather.

But, as our protagonist – a young man named Jonas – quickly discovers, the community is no utopia. Despite the apparent order and tranquility, all is not well.

In an ideal society, ordered liberty reigns. In Jonas’ community, the Committee of Elders – the governing body – has established an authoritarian regime under which order prevails, but individual liberty is virtually non-existent. Citizens are told what to wear, what means of transportation to utilize (bicycles), what careers to undertake and even whom to marry. Children must be applied for, and they are assigned to “family units” by the Elders. Each family unit is limited to two children.

In the community, there is neither color nor music. The sun never shines, and there are no animals. Yet, Jonas and his fellow citizens are none the wiser: They have been deprived of memory. They are only vaguely cognizant of “Elsewhere,” a mysterious place into which lawbreakers, the elderly, and the unwanted are routinely “released.”

Only one citizen – the Receiver of Memory – is aware that another type of society exists; that another, perhaps superior, mode of living is possible. But he is elderly and frail. The plot thickens when the Committee of Elders chooses 12-year-old Jonas as the new Receiver of Memory.

When the elderly, former receiver (aka The Giver) begins filling Jonas with memories, the latter endures pain and anguish, as expected. But he also revels in a world of color, bonds with animals, exults in the warmth of sunshine, gleefully sleds down a snow-covered hill, and most important, learns the difference between a “family unit” and a family. Jonas begins to question the nature of life in the community.

For instance, citizens are taught that a Ceremony of Release – particularly when performed for an occupant of the House of the Old – is a festive occasion. They celebrate without knowing the exact nature of a release, or precisely what happens to the happy honoree. But the Elders know. And so does The Giver.

Eventually, Jonas does, too. The pivotal moment in the book is a gut-wrenching scene in which Jonas witnesses a Ceremony of Release for an infant. The gruesome procedure is performed by one of the community’s most respected Nurturers, or caretakers of newchildren: Jonas’ father. When Jonas discovers that Gabriel, an “Inadequate” infant to which he has become attached, is also scheduled for release, he takes decisive action in defiance of the community. Fortunately, the edge-of-your-seat action that follows is only the beginning: there are three more books in the series.

The Giver won the Newbery Medal in 1994, and it’s easy to see why. Lois Lowry is a gifted and imaginative writer. This book should be mandatory reading in every American middle/high school.

- Charles Davenport Jr. (cdavenportjr@hotmail.com) is a freelance writer in Greensboro.