Like Tom Dillon, I’ve seen red wolves. Years ago, when my older son spent several summers helping with biological research at Cade’s Cove in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, he took us to see a few wolves that were kept in pens as part of the reintroduction effort there. Then one day when I had gotten temporarily separated from the rest of my family on a hike in the Cade’s Cove area, a wolf loped across my path, staring me down as he or she passed. That was unforgettable.

Dillon, an old friend who is a fine nature writer, reviews a new book about the efforts to bring back the red wolves that once roamed coastal North Carolina.

Reviewed by Tom Dillon

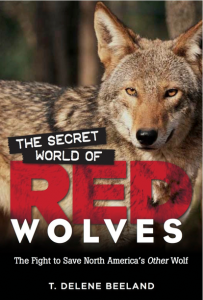

THE SECRET WORLD OF RED WOLVES. By T. Delene Beeland. University of North Carolina Press. 256 pages. $28 .

You don’t forget your first up-close encounter with a wolf. Mine came accompanying a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Officer on the Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge. I was there to do a story, but I was the only person with the officer when he discovered a trapped wolf that had dragged itself into a canal and was hypothermic. I had to help the officer rescue the wolf and get it into a cage.

You don’t forget your first up-close encounter with a wolf. Mine came accompanying a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Officer on the Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge. I was there to do a story, but I was the only person with the officer when he discovered a trapped wolf that had dragged itself into a canal and was hypothermic. I had to help the officer rescue the wolf and get it into a cage.

What I remember best is the wolf’s distrusting yellow-green eyes after we had safely deposited the cage back at the depot where the Red Wolf Recovery Program had its headquarters. We may have rescued the animal, but it clearly wanted no part of us.

I’ve thought ever since that someone should do a book-length report on the Fish and Wildlife Service’s effort to bring back this cousin of the storied gray wolf, and I was glad to see that Asheville nature writer T. Delene Beeland has taken on the project.

Beeland spent the better part of two years shadowing the biologists who work with the recovery effort, which is centered on the wildlife refuges of the Albemarle-Pamlico Peninsula in eastern North Carolina. She had unparalleled access to their records, as well as a reserved shotgun seat on many of their trucks as they bounced around the sand roads of the peninsula farms and forests.

What has emerged is a very good, detailed look at the now 27-year-old effort to bring back one of the most endangered animals on the continent. That covers the trapping of the last red wolves in Texas, a captive breeding program at several locations and the reintroduction of wolves at locations including the Great Smoky Mountains, Cape Romain refuge in South Carolina and elsewhere.

Today the program operates out of the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge, and it has had ups and downs. Wolf “howls” have become popular tourist attractions on the Dare County mainland on summer evenings, and wolves can help control the spread of animals such as nutrias, South American rodents that have become a problem in the wetlands of the coastal plains.

(For more on the usefulness of wolves, you might reread Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac. Leopold says, in part, “I now suspect that just as a deer herd lives in mortal fear of its wolves, so does a mountain live in mortal fear of its deer.” In other words, maybe a predator or two wouldn’t be a bad thing controlling excess deer.)

On the other hand, some people think the red wolf is not a distinct species, some farmers worry about predation and some hunters have trouble distinguishing red wolves from coyotes, though the wolves are much bigger. There have been two recent reports of wolves shot dead on the peninsula; $2,500 rewards are offered for information in the shootings.

People who lease land for deer hunting may worry that the wolves will affect their livelihood, despite the still small number of wolves; it’s estimated at 100 to 120. There’s also latent grousing about the federal use of land. The program can use up to 680,000 acres of federal and state land in Washington, Hyde, Tyrrell, Dare and Beaufort counties.

A bigger problem may be the apparent apathy in the staff of the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission toward the whole effort. Beeland quotes one commission biologist to the effect, “I’m not sure what purpose the red wolf serves that the coyote doesn’t.” In North Carolina, for the record, it’s OK to shoot a coyote any time.

Perhaps the most intriguing part of the book, to me, was a chapter interviewing residents of the peninsula, pro and con. Beeland talked with Kelly Davis, a former wildlife biologist with whom I used to work when I lived nearby, and she talked with hunters, land managers and farmers. Some of them seemed to feel the debate is in the past; I hope that’s true.

“We’ve seen three-dollar gas before, and we got used to it,” said one private wildlife land manager. “We don’t like it, it’s an inconvenience, but now we just don’t bitch about it.” The wolves may be, he said, like three-dollar gas.

There are a few parts of the book I took issue with. Much of it is written in present tense, an old editor’s hang-up, and I wondered about a chapter on the peril of rising sea level. To me, there are much more immediate concerns.

But I do like Beeland’s conclusion to this remarkable story: “I am hopeful that future scientists and citizens will see fit to conserve what we have left of canis rufus as a living reminder of both what was and what still can be.”

- Tom Dillon is a journalist and outdoor writer who lives in Winston-Salem.

One response to “The wolves in our woods”

Tom and Linda, thank you very much for your kind review here. I’m a little late in finding it; but these days, with a small toddler in tow, I find myself late for most everything. I’m glad you enjoyed the chapter on residents of the Albemarle Peninsula, that was one of my favorites too. Red wolves fascinated me from the first time I heard of them, it was a privilege to research and write this book. It looks like each of you had first-hand experiences meeting wolves which you can remember and cherish — but not everyone is so lucky. I hope that the first-person scenes and anecdotes provided in the book can make anyone feel as if they too had a special moment, standing somewhere in the deep woods and swamps of the N.C. Coastal Plain, when they encountered a rare, wild red wolf.