Would we recognize evil if we saw it walking around? Tom Dillon, a veteran newsman himself, takes a look at a book about American journalists and others who witnessed firsthand the rise of Hitler’s Nazi Germany.

By Tom Dillon

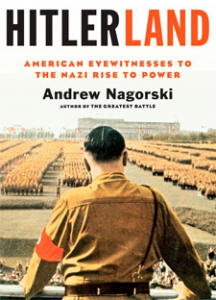

HITLERLAND: AMERICAN EYEWITNESSES TO THE NAZI RISE TO POWER. By Andrew Nagorski. Simon and Schuster, 2012. 385 pages, $28 hardback.

Hindsight is easy, but foresight is difficult. That’s true throughout history, but perhaps nowhere more so than in the reactions of Americans in Germany in the 1920s and ’30s to Adolph Hitler’s nascent “thousand-year reich.”

Hindsight is easy, but foresight is difficult. That’s true throughout history, but perhaps nowhere more so than in the reactions of Americans in Germany in the 1920s and ’30s to Adolph Hitler’s nascent “thousand-year reich.”

U.S. Ambassador William E. Dodd realized what Hitler was about, even if his warning fell on deaf ears at the U.S. State Department. Erik Larson well told Dodd’s story last year in his book, “In the Garden of Beasts,” which should be required reading for those who would understand Hitler’s Germany. (It’s reviewed in an earlier post on this blog by Paul O’Connor; just use the search function.)

William Shirer, a correspondent who would later pen the seminal “Rise and Fall of the Third Reich,” also had the necessary foresight to see what was coming, as did journalist Dorothy Thompson and others. But that was not true of everyone.

Take, for instance, the Harvard University grad with German lineage and an American wife; he became an early aide to the Fuehrer. Others were blind, some – Henry Ford and Charles Lindbergh come to mind – were apologists, and a few were out-and-out propagandists. Six of those were later indicted in the U.S. for treason.

How Americans in Germany responded to Hitler’s rise is the subject of Andrew Nagorski’s book, and it’s a good expansion of Larson’s earlier work. It’s not as novelistic in concept – indeed, that would probably have been impossible. But Nagorski tells the whole story from Hitler’s attempted “Beer Hall Putsch” coup attempt in 1923 to the expulsion of captive American journalists and diplomats in 1942.

Unless you’re an astute student of the era, you’ll find some new stories here, like the American woman who kept Hitler from a suicide attempt when the authorities closed in after the Beer Hall Putsch in Munich.

That woman was Helene Niemeyer Hanfstaengl, whose husband Ernst, or “Putzi,” had graduated from Harvard, returned to Germany and then latched onto a job basically explaining Hitler to foreigners, particularly the press. Hanfstaengl was “monumentally vain,” even after he was almost dispatched by Hitler in the ’30s. Thompson called him “the oddest imaginable press chief for a dictator” and “an immense, high-strung incoherent clown.”

Hanfstaengl stories are rife both here and in Larson’s earlier work, but he’s really a sideshow. Americans visiting Germany in the ’20s and ’30s included all sorts of famous names: Howard K. Smith, later of ABC News; Thomas Wolfe, the North Carolina author; newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst; Richard Helms, who would later lead the CIA; athlete Jesse Owens, famed for his victories at the 1936 Berlin Olympics; and even the black sociologist W.E.B. DuBois.

Indeed, duBois’s report of his travels may explain some of the early-on American confusion about Nazi Germany. DuBois wrote, “I have been treated with uniform courtesy and consideration. It would have been impossible for me to have spent a similarly long time in any part of the United States without some, if not frequent, cases of personal insult or discrimination.”

Besides Dodd and Shirer, the heroes, if you will, of this tale are usually the journalists, now mostly part of history, who could help their reluctant countrymen understand the nature of Nazi Germany as it eliminated political opponents, instilled hatred of the Jews and readied the German military machine for its world conquest.

Just a few of those, in addition to Shirer, Smith and Thompson, are Louis Lochner of the Associated Press, Edgar Mowrer of the Chicago Daily News, radio broadcaster H.V. Kaltenborn, and Karl von Wiegand of Hearst newspapers, the first newsman to interview and write about Hitler.

These people were “lucky to be able to observe firsthand the unfolding of a terrifying chapter of the modern era,” says Nagorski, a former longtime Newsweek correspondent who is now the vice president of New York’s East-West Institute.

They were even luckier to be Americans, which meant they could observe what was happening from a protected vantage point. Says Nagorski, “They were truly privileged eyewitnesses to history.”