Bob Moyer loves New Orleans and visits often. Here he reviews a book about a side of New Orleans most tourists don’t visit, a book about “people that people don’t write books about.”

Reviewed by Robert P. Moyer

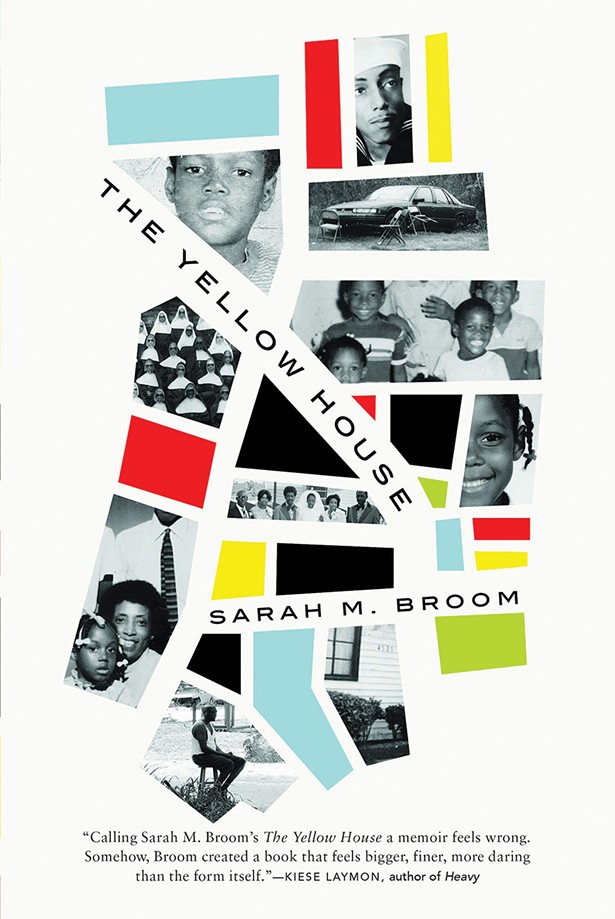

THE YELLOW HOUSE. By Sarah M. Broom. Grove Press. 304 pages. $26.

New Orleans has certain phrases that are — well, New Orleans. “Where y’at?” Is a common greeting. It’s also common for people to chant “Where you from?” to people parading through neighborhoods, second-lining behind parades. Sarah Broom would give a loud, emphatic answer to that chant — NEW ORLEANS EAST.

That’s where The Yellow House she grew up in with 11 brothers and sisters was located. New Orleans East shouldn’t even exist. Swampland, below sea level, cut through by ill-advised waterways, developed by greed, grossly mismanaged by government, New Orleans East was no kind of tourist destination. No one ever headed off I-10 West to see the sights of Chef Menteur Highway, especially the half-street known as Wilson where the yellow house was located. In this marvel of a memoir, Sarah “Monique” Broom mixes family history, oral history, political deviance, city portrait, and personal memoir — sometimes all on the same page. Reflective at times, riveting at others, this book is about people that people don’t write books about. Like many families, the 11 children either worked at the local NASA facility, or took the bus 15 miles into the city to take care of the tourists in hotels, restaurants and bars. New Orleans East was “…a city where being held up while getting out of your car is the norm, where many children graduate from school without knowing how to spell, where neglected communities exist everywhere, sometimes a stone’s throw from overabundance.” Long before Katrina, local residents were familiar with the “waters,” surging into the swamp of a city through commercial waterways. One of Broom’s brothers remembers learning to swim from their house to the shop on the corner. But — it was her home.

And then came Katrina. The most peripatetic of her family (she travels to New York, Burundi, Paris, Berlin and other parts of the world during the course of the book), Broom watched the flood from a distance. She wasn’t surprised, however: “Those images shown on the news of fellow citizens drowned, abandoned, and calling for help were not news to us, but still further evidence of what we long ago knew.” For her, and most of the people in New Orleans, Katrina and its aftermath were “…a metaphor for much of what New Orleans represents: blatant backwardness about the things that count.”

Before Katrina, 11 members of her family lived in New Orleans. After Katrina, only two remained, and that number stayed that way. Broom left again and again, only to return. A constant theme in her narrative is the struggle to be “from” New Orleans while leaving so often. The Yellow House is at the center of the family’s life, even when the city tears it down. It is only then that she comes to terms with the loss of that center: “I had no home. Mine had fallen all the way down. I understood, then, that the place I never wanted to claim had, in fact, been containing me. We own what belongs to us whether we claim it or not. When the house fell down, it can be said, something in me opened up. Cracks help a house resolve internally its pressures and stresses, my engineer friend had said. Houses provide a frame that bears us up. Without that physical structure, we are the house that bears itself up. I was now the house.”

It takes 11 years for Broom’s mother to get a settlement for her house, and then that sum was based on pre-Katrina value, not what it would cost to replace it. When Ivory Mae sells the property, a palpable sense of true loss permeates the conclusion. Broom has captured in the history of The Yellow House a history of a whole generation, and an homage to the people who lived in New Orleans East, then and now.